Should you go for it? A base steal predictor for the MLB

One of the most exciting things in baseball is the base steal. There are two outcomes, if the base runner times it properly:

or they don’t:

Sometimes even something amazing can happen, look at this play by Jayson Werth:

Base stealing is a calculated gamble, where game situation dictates the chances for success. To make the decision on whether or not go for it requires sound judgement from both the base runner and the manager, judgement only gained from playing decades of high level baseball. However, what if this decision could be made just with the click of a button? I decided to try to do this by building a predictive model for my 3rd Metis project and created a Flask app that was deployed on Heroku.

Data:

Acquiring Data:

To build this model I needed many examples of base stealing situations and their outcomes. Luckily Kaggle had such a data set that was provided by Sportsradar. Hosted on Google’s Bigquery platform, this MLB data set contained information on every play from the 2016 season. I ended up uploading this data to a PostgreSQL server as the initial dataset contained 760,000+ rows and 145 features, which would be too large to load into my local memory.

One initial quirk in exploring this data set was trying to pull just base steal events. Initially I tried to find them by just doing a wildcard search for ‘steal’ in the descriptions:

SELECT *

FROM baseball

WHERE description LIKE '%steal%';

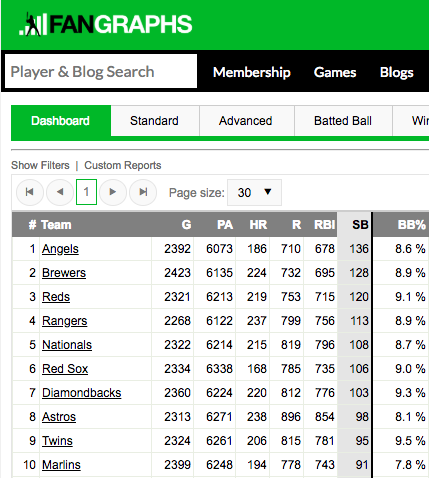

However this query was too small as it only returned 500 entries. As an example, the top 10 teams leading the 2017 MLB season in stolen bases had totals of:

So only 500 entires would be too low. Digging deeper, I discovered that multiple base stealing events were missing information in their descriptions. Thus, I ended up querying the steal events by using:

SELECT *

FROM baseball

WHERE rob1_outcomeid LIKE '%CS%'

OR rob1_outcomeid LIKE '%SB%'

OR rob2_outcomeid LIKE '%CS%'

OR rob2_outcomeid LIKE '%SB%'

OR rob3_outcomeid LIKE '%CS%'

OR rob3_outcomeid LIKE '%SB%';

As each rob (runner on base) had an outcome id, by looking for the presence of either ‘SB’ (stolen base) or ‘CS’ (caught stealing) I was able to grab the steal events.

With 145 features, there was a lot of information available for each play. While a lot of these features would end up not being predictive, there were a couple features that I thought were informative but not reflective of a real-time situation. For example, information on the pitch type, pitch speed, and pitch location would be very useful for a base runner. These features would allow a base runner to estimate approximately how much time they had to reach the next base. However, in the real world this information would not be available to the runner or manager so I decided to restrict these features from the model.

As a substitute, I joined my dataset with player statistics from Fangraphs. Specifically I utilized the pitcher pitch type distribution statistics as a proxy for the pitch type and velocity, while the hitter plate discipline statistics was a proxy for pitch location. This is a reflective of how a base runner would be guessing what pitch the pitcher would throw based on their past tendencies.

Data Cleaning:

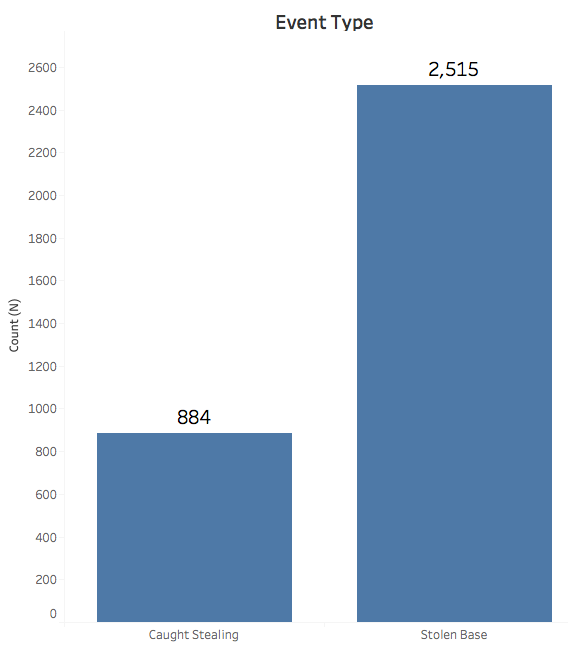

While the Sportsradar data was comprehensive, I still needed to clean the data. The dataset contained 760,000+ entries which I had to filter to only base steals events. I took out any pickoff events or events in the post season. My reasoning was that pickoffs are different from a normal steal attempt and that post season behavior is different from regular season behavior. These data cuts left me with 3000+ base steal events:

Many features like gameID, attendance, venueName were also excluded as I felt they would not be predictive.

Data Imputation:

Besides subsetting there were entries where the pitcher or hitter stats were missing. This occurred when the listed pitcher or hitter were missing from the Fangraphs stats. This was to be expected because of the year difference (2016 vs 2015) in data sets. It is reasonable to assume that there are 2016 players that did not play in 2015 (like rookies). To account for these missing values, I ended up imputing those features with the respective median value as calculated from the training data.

Feature Generation:

With the large number of categorical variables, I ended up having to dummify a lot of features to make them interpretable to my models. In doing so, I made sure to not fall for the dummy variable trap (DVT). For instance, to determine the handedness of a hitter I created one column ‘is_hitter_R’ instead of two as that would fall into the DVT for this data set (there was only one hitter that was ambidextrous).

The other type of feature engineering that I utilized involved box-cox transformations. Many of the player statistic features were not normally distributed and tightly grouped, so to rectify that I applied a box-cox transformation where each feature was transformed with an optimized lambda.

Modeling:

Optimization Metric:

As a manager, there would be multiple possible metrics this application could try to optimize for. First would be to maximize the number base steals (minimizing false negatives), however such a strategy could be too risky as that could result in too many outs. Second would be to minimize caught stealing events (minimizing false positives), however this strategy could be too passive and not take advantage of possible scoring opportunities. Instead I decided to optimize for F1 which would bring a balanced approach:

Model Selection:

In maximizing F1 after experimenting with other models, two models performed the best: Logistic Regression (LR) and Gradient Boosted Trees:

| Model | Training F1 |

|---|---|

| Dummy Classifier (Stratified) | 0.749 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.937 |

| Gradient Boosted Trees | 0.938 |

Both models ended up with similar F1 scores on the training set. Therefore I chose a LR model for two reasons: LR model’s feature importance is easier to interpret and the run time of the LR model was faster. The latter would be important if I was trying to deploy a real time app.

Feature Importance:

From the LR model, these were the most important features for each outcome:

| Stolen Base | Caught Stealing |

|---|---|

| If runner is on 1st base | Batter: Contact % (BC) |

| Batter: Swing % outside zone (BC) | Batter: Swing % (BC) |

| Batter: First pitch strike (%) | Pitcher: % of Change-up Pitches |

BC refers to the box-cox representation of the feature

The most dominant feature was whether or not the base runner was on 1st base. Out of all of the features it appeared to be twice as predictive as the next closest. This makes sense physically as a base runner on first base would have a better chance to steal a base one on any other base.

Model Performance:

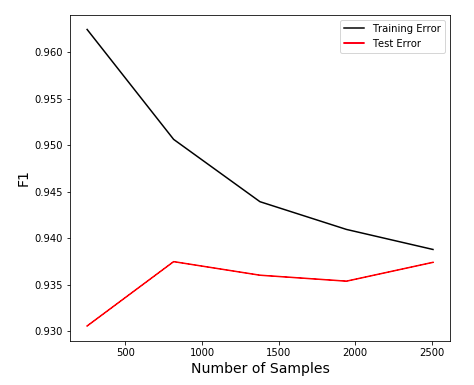

My LR model’s test F1 score was 0.924. The small difference from the test score meant that my model was generalizing well to new data and not overfitting. This was reinforced by the learning curve:

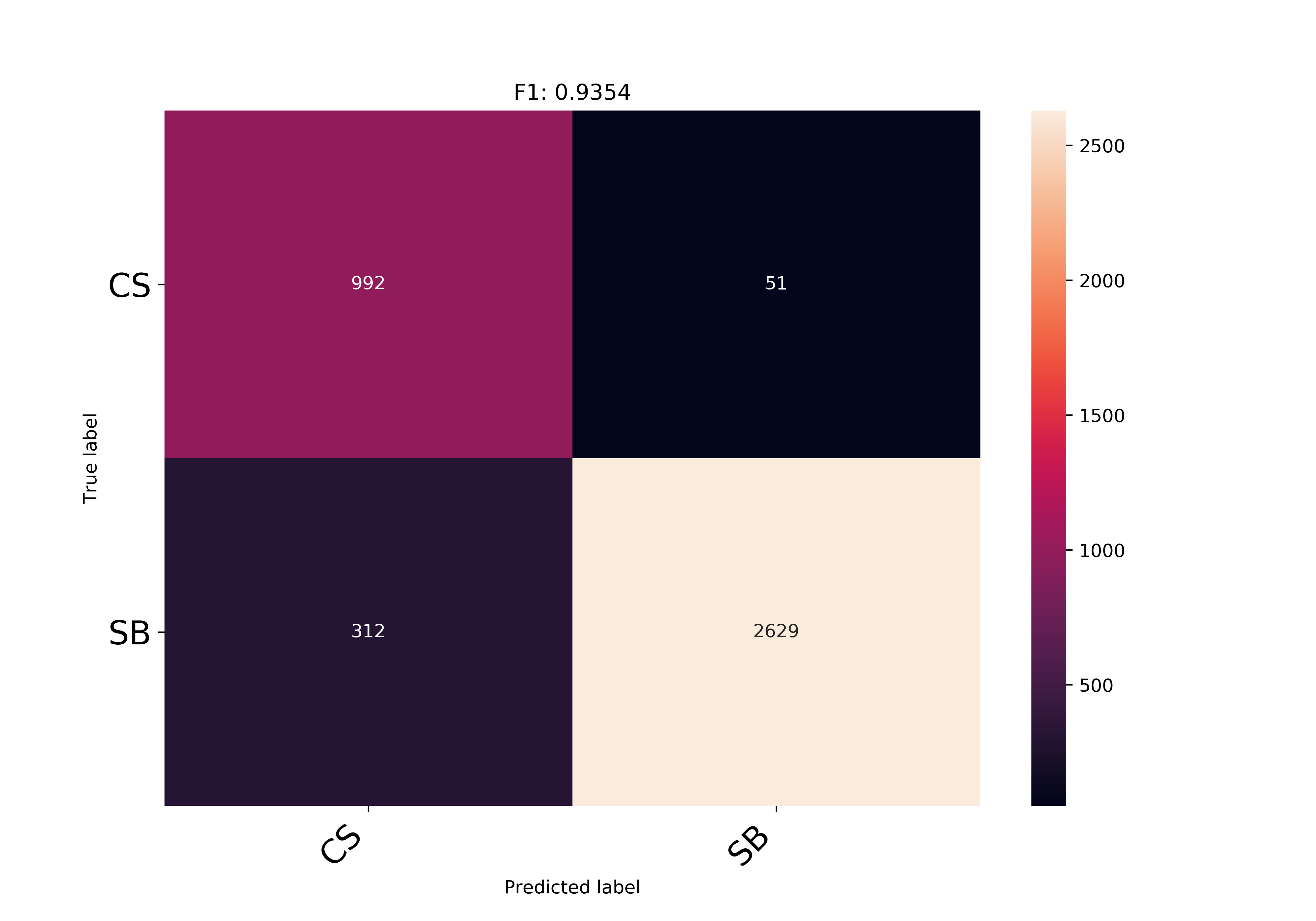

Retraining the model on the full data set, it was able to generate the following confusion matrix:

With a final F1 score of 0.9354, the model performance ended up right between the training and test F1 scores. One way to interpret these results would be to equate the number of caught stealing (CS) events to runs that would have been saved. With 922 CS events that the model was able to classify, a ballpark estimate of runs saved would be 123 runs. I utilized the this runs table I found online to translate the game situation of each steal attempt (dividing by 2 to be conservative).

With this model I also ended up building an interactive Flask app that would do predictions based on user selected inputs as shown:

If you would like to play with it yourself you can access it here.

Future Work:

While I ended up with a working model, there were a few improvements that I could implement if I wanted to extend this project further:

-

Multiple base runners: With the current model, it is only accurate for predicting singular baserunner events. While it can predict the successfulness of a base being stolen if there are multiple baserunners, the predictions don’t account for multiple outs.

-

Runner information: My model currently does not account for the base runner’s ability. Thus, I would have like to include base running statistics for the runner on base. Some statistics that could be utilized would be the amount of bases that a baserunner had stolen the previous year and metrics like their 40 yard dash time.

-

More data: I believe access to more data would help improve this model greatly. If I had gotten data from other MLB seasons to rectify the imbalance between CS and SB events, I believe that I would have found more predictive features.

The code and data for this model and Flask app are available at my Github repo.